Prelude to the Ardennes: Why Hitler Chose to Attack in the West

Strategic Goals

By late 1944, Nazi Germany was being squeezed on two fronts – the Soviets pushing from the east and the Western Allies pressing from the west. Adolf Hitler believed a bold counteroffensive in the west could dramatically shift this balance. His primary military objective was to launch a surprise attack through the Ardennes Forest, seize the vital port of Antwerp, and split the British and American armies. Hitler envisioned encircling and destroying Allied forces north of the Antwerp-Brussels line – essentially aiming for a second Dunkirk in Germany's favor. If successful, such a blow would cripple the Allied supply lines and isolate the British 21st Army Group, hoping to force a negotiated peace in the West.

Politically, Hitler hoped that a shattering defeat might fracture the Anglo-American alliance. He felt the relationship between the U.S. and Britain was fragile and could "fall apart" under a major crisis, which would then allow Germany to focus all its forces against the Soviet Union. In essence, Hitler's strategy was to "stop the Allied use of Antwerp and split the Allied lines", compelling the Western Allies to the negotiating table. This Ardennes counteroffensive, code-named Wacht am Rhein ("Watch on the Rhine"), was thus conceived as a decisive gamble to reverse Germany's fortunes.

Hitler's broader war strategy at this stage hinged on the belief that victory – if it was still attainable – would come in the west. The German High Command knew the eastern front offered no real prospects of halting the Red Army's inexorable advance. However, they perceived the Western Front as more fluid, with the possibility that a dramatic attack could shock the Allies. Hitler declared that this "now or never" offensive would decide Germany's fate. He hoped a victory in the Ardennes might buy time or even persuade the Western Allies to consider a truce, allowing him to redeploy forces to crush the Soviets. Thus, militarily and politically, the Ardennes offensive was Hitler's attempt to achieve several goals at once: regain the initiative, protect the Rhineland industrial region, shatter Allied morale, and force a split in Allied cooperation. It was an all-or-nothing bid to change the course of the war.

German Leadership Decisions

Within the German high command, the plan to strike through the Ardennes was met with deep skepticism and internal disagreements. Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt (Commander-in-Chief West) and Field Marshal Walter Model (Army Group B commander) both felt Hitler's plan was far too ambitious given Germany's depleted resources. After studying the Führer's proposal, Rundstedt and Model advocated for a more limited counterattack – later dubbed the "Small Solution" – instead of Hitler's grand plan (the "Big Solution").

The Small Solution envisioned a more modest offensive that would attack the Allies in a pincer east of the Meuse River (for example, aiming to retake Liège) without driving all the way to Antwerp. Rundstedt bluntly observed that "all, absolutely all conditions for the possible success of such an offensive were lacking" and that capturing Antwerp was well beyond German capabilities. He reputedly exclaimed, "Antwerp! If we reach the Meuse we should get down on our knees and thank God – let alone trying to reach Antwerp!", underscoring his belief that the original objectives were utterly unrealistic.

Field Marshal Model shared Rundstedt's pessimism. In private, Model confided that Hitler's plan "hasn't got a damned leg to stand on" and estimated it had "no more than a ten percent chance of success". He and Rundstedt lodged formal protests and alternative proposals to Berlin, warning that the timetable (crossing the Meuse in just a few days and reaching Antwerp shortly thereafter) was unreasonable.

General Hasso von Manteuffel, who was appointed to command the Fifth Panzer Army in the coming offensive, also had serious reservations. Manteuffel supported the idea of a concentrated attack but on a narrower scale; like Rundstedt and Model, he believed the forces available were insufficient to reach Antwerp. In late October and November 1944 planning meetings, Manteuffel and even Hitler's favorite SS commander, Sepp Dietrich, sided with Model in urging Hitler to scale back the operation's aims. They argued for focusing on a smaller encirclement east of the Meuse rather than a deep thrust to the coast.

Despite these candid objections from his top generals, Hitler overruled them. He ridiculed the Small Solution as a timorous "half measure" that could never deliver a decisive victory. Hitler was adamant that Antwerp remain the objective – the linchpin of the entire operation – even though Jodl and others warned him that the goal was "disproportionate to our available forces". With characteristic intransigence, Hitler issued an edict that "There will be absolutely no change in the present intentions".

In early December 1944, Model made one last attempt to convince Hitler to adopt the more limited plan, even bringing Dietrich and Manteuffel to personally voice their concerns. Hitler refused to budge. Having silenced dissent, Hitler demanded total obedience – his generals were to execute Wacht am Rhein exactly as he envisioned. The internal discord would give way to a grim resolve: despite privately harboring doubts, commanders like Rundstedt and Manteuffel resigned themselves to Hitler's directive. "We stake our last card – we cannot fail," Rundstedt echoed dutifully, in line with Hitler's wishes.

Hitler's Gamble

Hitler pressed forward with the Ardennes offensive because he saw it as a last, decisive opportunity to alter the war's trajectory. In his mind, several factors converged to make this gamble worth the risk. First, the Wehrmacht had managed to scrape together a sizable, if motley, force for the operation. By diverting units from quiet sectors and the strategic reserve, Germany assembled about 30 divisions – including elite panzer divisions and newly formed Volksgrenadier divisions – for the attack.

Hitler took personal comfort in these numbers and repeatedly assured his doubting generals that ample resources would be provided. He promised, for instance, up to 1,900 aircraft to support the assault, including a force of the new Me-262 jet fighters which he touted as "far superior to anything the Allies could put in the air". Further, at Hitler's insistence, General Keitel vowed that 4.25 million gallons of fuel and thousands of tons of ammunition would be stockpiled to fuel the drive west. Hitler brandished these commitments as proof that, this time, the offensive would not stall for lack of supplies or air cover as some feared. In short, he staked what remained of Germany's men, tanks, fuel, and planes on one bold stroke – a classic gamble that he believed could still pay off.

Crucially, Hitler was counting on surprise and timing to neutralize the Allied advantages. He planned the attack for late fall/early winter, when the notoriously rugged Ardennes terrain was made even more daunting by snow and mud. This was intentional – his meteorologists had selected a window when "at least ten days of continuous bad weather" could be expected. Hitler gleefully noted that if the weather grounded Allied aircraft, his troops could move under cover of darkness and forest without fear of the overwhelming Allied air superiority. As he told his senior staff, the offensive would "begin in a bad-weather period when the enemy air force is grounded", leveling the playing field for the German side. Poor visibility and short winter days, Hitler believed, would negate one of the Allies' biggest advantages and allow his panzer spearheads to achieve a breakthrough before the enemy could react. This emphasis on timing was a key part of Hitler's gamble – he was effectively betting that nature (in the form of fog, rain, and snow) would act as an ally to the Germans.

Hitler also convinced himself that the Allied command was complacent and unprepared for a major counterstrike. Through intelligence and observation, he knew the Americans regarded the Ardennes sector as a relatively "quiet" front. In fact, only a handful of U.S. divisions – many of them exhausted from earlier fighting or brand-new and untested – were thinly spread across an 80-mile front in the Ardennes. "The present front can easily be held," Hitler remarked, noting that four U.S. divisions (the 4th, 28th, 99th Infantry, and 106th, along with an armored cavalry group) were covering a vast, forested region. He intended to smash through this weak line with over ten times the number of tanks the Americans had in the sector.

Hitler saw the Allied order of battle in December 1944 as vulnerable – their supply lines were stretched, their units in the Ardennes were under-strength, and Allied leaders were firmly on the offensive, not expecting a massive German counter-offensive on the very ground they had designated for R&R and refit. This miscalculation by the Allies was exactly what Hitler hoped to exploit.

Despite his optimism, the risks of Hitler's plan were enormous. Many of these risks were pointed out by his own commanders, only to be brushed aside. SS General Sepp Dietrich – who was to lead the Sixth Panzer Army in the assault – famously described the daunting odds stacked against the operation.

"All I had to do was to cross the river, capture Brussels, and then go on and take the port of Antwerp, through the Ardennes where the snow was waist-deep and there wasn't enough room to deploy four tanks abreast, let alone six panzer divisions; … and at Christmas time."

The terrain, the weather, the logistics, and the timeline were all against the Germans. As Dietrich summed up his reaction to the plan, "I can't do it," he exclaimed. "It's impossible!"

Indeed, the offensive's success hinged on many unlikely factors falling perfectly into place: the weather staying poor (yet not so poor as to bog down German vehicles), a lightning-fast capture of Allied fuel depots to keep the panzers rolling, and an unbroken string of German battlefield victories over several weeks. Any delay or stout resistance could derail the tight timetable. If the offensive failed to achieve a strategic breakthrough in the first 48–72 hours, Germany would have expended its last reserves for little gain and left itself exposed to Allied counterattack.

Hitler understood these risks but was undeterred. He believed his force of will and surprise could overcome the material disadvantages. As he told his generals, this offensive was "to decide whether we shall live or die… the enemy must be defeated – now or never." In Hitler's mind, the very desperation of Germany's situation meant there was no alternative but to take this gamble. It was a high-stakes throw of the dice – one last attempt to snatch victory (or at least a stalemate) from the jaws of defeat.

Why the Ardennes?

Hitler's choice of the Ardennes Forest as the attack route was influenced by both strategic logic and historical precedent. The Ardennes region (bordering eastern Belgium and Luxembourg) had dense forests, hilly terrain, and limited roads – features that might seem to hinder a mechanized assault. However, these same features offered the Germans a chance to achieve tactical surprise. The Allies considered the Ardennes "an unlikely site for a counterattack" due to the inhospitable terrain. In fact, Allied high command had designated the Ardennes sector as a quiet zone where battered divisions could recuperate and green units could get their first exposure to the front.

Thus, in December 1944, this sector was thinly held and relatively complacent. American units guarding the Ardennes were spread out, with frontage five times wider than normal in some cases. Patrols and intelligence reports did note increased German activity in the Eifel region just across the border, but these warnings were largely dismissed by Allied commanders as enemy desperation or defensive measures. The Germans also took extraordinary measures to maintain secrecy – avoiding radio communications (so ULTRA intercepts would yield nothing) and moving troops and supplies only at night or in bad weather. By choosing the Ardennes, Hitler attacked where the Allies least expected. When the offensive struck, it achieved almost total surprise, in large part because the Allies had believed such a massive operation in this rugged area and in winter was not feasible.

There was also a powerful historical precedent behind Hitler's choice of the Ardennes. Just four years earlier, in May 1940, the German Army had launched its attack on France through the same forested region. In that campaign, German Panzer divisions had famously channeled through the Ardennes – bypassing the heavily fortified Maginot Line – and achieved a surprise breakthrough that led to the fall of France. Hitler never forgot this stunning success. In 1940, the Allies had assumed the Ardennes was impassable for tanks, and they were caught off guard. Now in 1944, Hitler aimed to repeat the stratagem: drive armor through the woods where the enemy thought it weakest. "Just as they had done in 1940, tanks were to smash through Allied lines in the Ardennes forest and head for the coast," one historian notes of Hitler's plan. The goal again was to reach the Channel ports and trap Allied forces.

The geography was essentially the same, but circumstances were different – it was winter, and the Germans had far fewer tanks and planes. Still, Hitler believed the Ardennes offered the best chance for a decisive surprise. The terrain, while difficult, also meant Allied movement would be constricted once the attack began, potentially channeling the Allied response and slowing any counter-maneuvers. Additionally, the Ardennes lay along the seam between the British and American armies. Hitler hoped to split the Allied front at this juncture, driving a wedge between British forces to the north and American forces to the south. If his armies could punch through to the Meuse River and beyond, they would turn north toward Antwerp, cutting off the British 21st Army Group in Belgium from the U.S. armies in the Ardennes and France. This "split" at the seam of the Allied lines was a core element of the plan, intended to sow confusion and paralyze the coordination between Allied commanders.

In summary, Hitler chose the Ardennes because it maximized German advantages of surprise, historic familiarity, and initial local superiority, while exploiting a point of relative Allied weakness. The dense forest and winter weather that seemingly made an offensive risky were, in Hitler's calculation, the very factors that would allow a battered Wehrmacht to move unseen and strike a thunderbolt blow where it was least anticipated.

Maps and Visual Aids

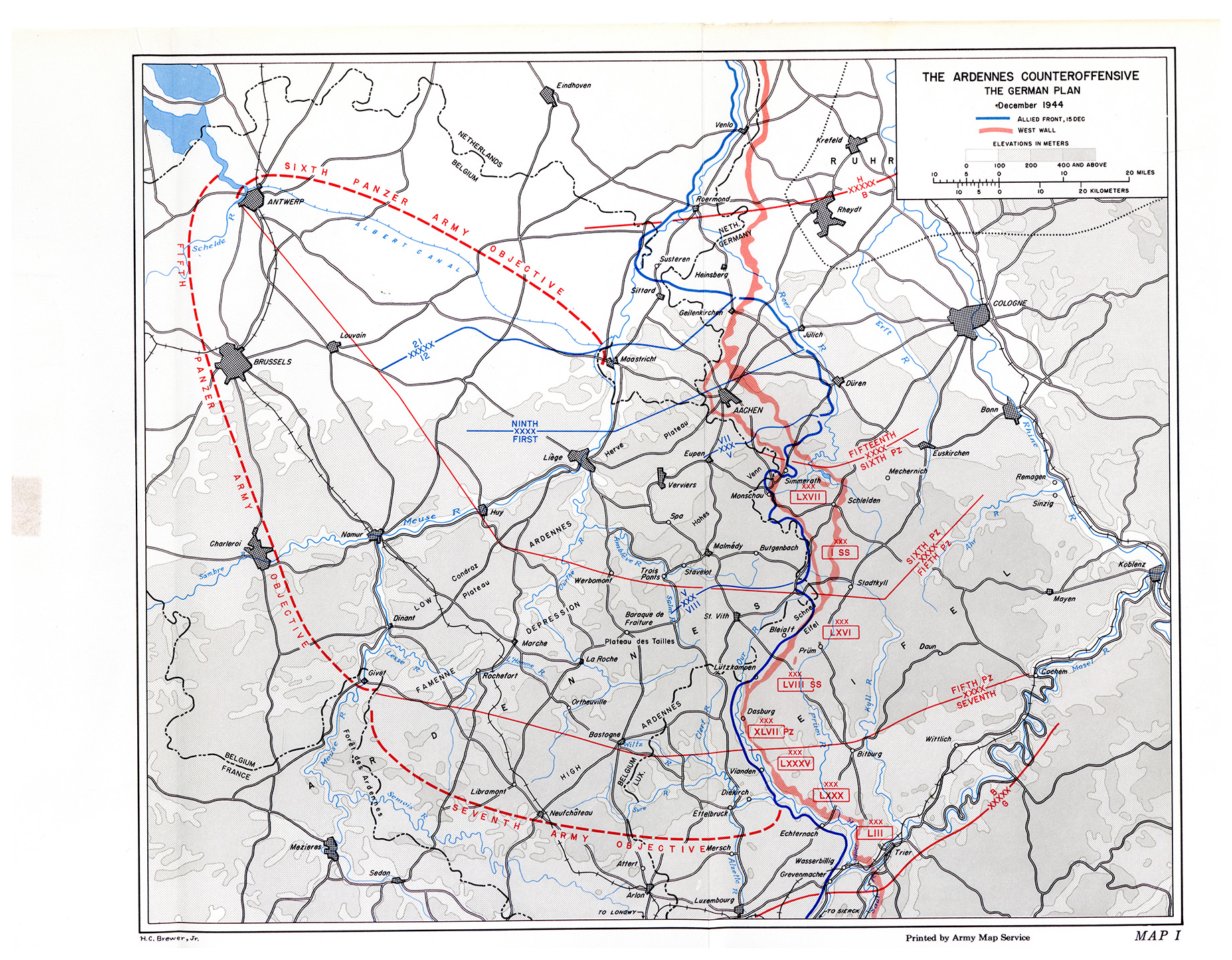

The German plan for the Ardennes counteroffensive (December 1944) called for a three-pronged attack across a 60-mile front. The northern thrust by 6th SS Panzer Army (red arrow at top) under Sepp Dietrich would drive west and then northwest toward Antwerp, aiming to cross the Meuse River and capture the vital port. In the center, 5th Panzer Army (middle arrow) under Hasso von Manteuffel was to push west toward Brussels, Belgium's capital, and shield the flank of the 6th by engaging Allied reserves. In the south, 7th Army (lower arrow) under Gen. Erich Brandenberger would advance just far enough to secure the offensive's southern shoulder, digging in to fend off any counterattack from General Patton's U.S. Third Army coming up from the south.

The dashed red lines on the map show the ambitious extent of the planned German advance – reaching Antwerp and the Scheldt estuary in the northwest and encircling large Allied forces in Belgium. The blue lines represent the Allied front positions at the start of the attack. This visual aid illustrates how the Germans intended to achieve a deep penetration and encirclement in the West. In reality, the offensive achieved initial success (creating the "bulge" in the lines) but never came close to the final objectives as depicted.

Quotes and Primary Perspectives

Throughout the planning and execution of the Ardennes offensive, participants on both sides recorded their candid thoughts, which illuminate the mindset behind this gambit:

"The Führer interrupts Jodl. He had resolved to mount a counterattack from the Ardennes, with Antwerp as the target... Split the British and American armies at their seam, then a new Dunkirk!... Our offensive will begin in a bad-weather period when the enemy air force is grounded."

This quote encapsulates Hitler's strategic aim (splitting the Allies and recreating a 1940-style victory) and his faith in surprise and weather to aid the German attack.

"This plan hasn't got a damned leg to stand on… The whole operation has less than a ten percent chance of success."

Model's blunt assessment highlights the profound doubts held by Germany's seasoned commanders – they recognized the plan's near-impossibility, even as they prepared to carry it out.

"All I had to do was to cross the river, capture Brussels, and then go on to take the port of Antwerp… and all this at the worst time of year and at Christmas time!"

Dietrich's sardonic summary lists the Herculean tasks demanded by Hitler and underscores the absurd difficulties (weather, terrain, timing) the German attackers faced. His exasperated follow-up – "I can't do it… It's impossible!" – reportedly voiced to his staff, shows even Hitler's favorites were alarmed by the operation's scope.

Allied Intelligence Assessments: Prior to the attack, Allied commanders largely misjudged German intentions. A U.S. Army intelligence report in early December 1944 noted increased German rail and troop movements but concluded that the Ardennes was "an unlikely site for a counterattack" given the terrain and the assumption that German reserves were too depleted for major offensive action. Some frontline American units had heard rumors from German POWs about a big attack coming, but these warnings were discounted as enemy propaganda or wishful thinking. As one American officer admitted later, "We didn't think the Germans had enough left to mount a large-scale attack – certainly not in that sector." This overconfidence, born of the Germans' apparent collapse after the Normandy and Market Garden campaigns, meant the Allies were indeed caught off guard on 16 December 1944.

"The forces available for Wacht am Rhein are extremely weak in comparison to the enemy… I have grave doubts whether it would be possible to hold the ground won, unless the enemy is completely destroyed."

Here Rundstedt recorded his official objections – essentially warning that even if the offensive gained ground, Germany lacked the strength to hold it against inevitable Allied counterattacks unless they achieved total victory. Nonetheless, when Hitler insisted on proceeding, Rundstedt gave the order to attack. Reflecting Hitler's do-or-die attitude, Rundstedt said grimly, "We stake our last card – we cannot fail."

These quotes from primary actors on each side vividly illustrate the mindset going into the Battle of the Bulge: Hitler's grand ambitions and fervent hope for a surprise triumph; his generals' deep misgivings and realism about Germany's odds; and the Allies' initial disbelief that the Germans could still muster such a punch. They set the stage for the desperate struggle that unfolded in the snow-covered forests of the Ardennes.

The "All or Nothing" Nature of the Attack

Hitler's Ardennes offensive was truly an "all or nothing" gambit. It represented Germany's final major reserves thrown into one basket – a last attempt to turn the tide of war or at least force a stalemate. In the words of Jodl (Hitler's operations chief), "In our present situation… we must not shrink from staking everything on one card." This mentality had clearly taken root at the highest level in Berlin. Hitler understood that a limited success would not save Germany at this late stage; only a spectacular victory had any hope of altering the outcome. That is why he was unwilling to consider half-measures.

"This battle is to decide whether we shall live or die," Hitler told his generals – a stark admission that Germany's fate hinged on the Ardennes attack. The offensive was launched with the expectation that it either accomplish something extraordinary (such as capturing Antwerp and forcing the Western Allies to negotiate), or Germany would face inevitable collapse. There was no middle ground. A senior German officer later described the plan as "our last card." Indeed, once the offensive began, there were no significant reserves left behind it; virtually everything the German Army in the west could scrape together was committed to the onslaught.

The consequences of failure would be dire – and they were. By mid-January 1945, it was clear the Ardennes gamble had failed. The German attack, though initially successful in creating a "bulge" in the Allied lines, never came close to achieving its strategic goals. Once the surprise wore off and the weather cleared, overwhelming Allied air power and reinforcements sealed the fate of the German offensive. Hitler had effectively spent the last strength of his western armies for no lasting gain. The German losses in the Battle of the Bulge – in men, tanks, aircraft, and precious fuel – were irreplaceable.

As a result, Germany's ability to resist the Allies was fundamentally broken. Within weeks of the Bulge, the Soviet Red Army launched its January 1945 offensive in the east, and the depleted German forces could offer only feeble resistance. The Soviets drove hundreds of miles towards Berlin, while in the west the Allies crossed the Rhine by March 1945. In effect, the failure of the Ardennes offensive sealed Nazi Germany's fate. Hitler's last gamble had been a costly flop that shortened the war by hastening the destruction of German military power on both fronts.

From the German perspective, the Ardennes offensive was the final "now or never" moment – after it, no other realistic opportunity to change the war remained. It was Hitler's last legitimate attempt to stop the Allied invasion of Germany. When it failed, the road to the Rhine and ultimately Berlin lay open. As Winston Churchill later noted, the Battle of the Bulge was "the greatest American battle of the war" – but for the Germans it was the last throw of the dice, an offensive fueled by desperation. Hitler had gambled everything in the West and lost. In the aftermath, even loyal commanders recognized that Germany's prospects were doomed. The Ardennes gamble stands in history as a classic example of an all-or-nothing offensive – bold in concept, briefly alarming in execution, but ultimately catastrophic for the initiator when its improbable aims went unrealized.